One’s aesthetic is a product of many factors: personal, emotional, experiential, educational, sociological, cultural, and religious. In my case, I prefer Chopin to Bach; Poe to Whitman; Runge to Mondrian; generally, but not perfectly, Romanticism to Neo-Classicism. I was born eighty-five years after the end of the American Civil War. I grew up in the 1960s in Mississippi, where specific segments of society had idealized, romanticized, and, in some cases, totally fabricated its past, refusing to deal with a painful and bloody history. Interestingly, Shakespeare, Scott, Byron, Alexander Dumas, and Hugo were the preferred authors in the American South before the Civil War; in the American North/Northeast, it was Goethe, Dickens, Longfellow, Schiller, and Byron, the latter being the only author shared between the two.

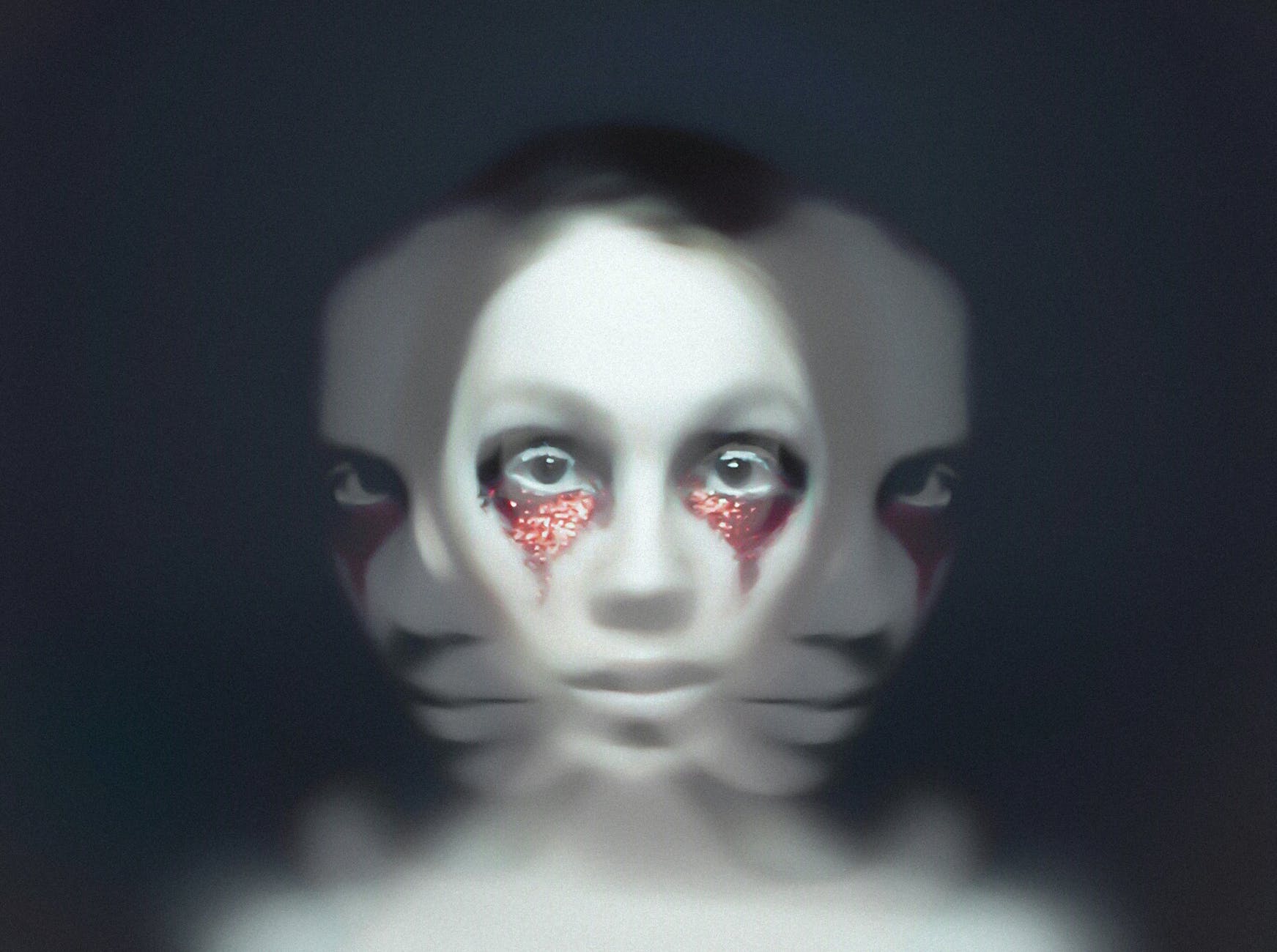

My love of literary Romanticism is driven, in part, by an abiding fascination with the supernatural, a medium that provides many poets, writers, and myth-makers a platform from which to delve into uncharted territories and evoke intense emotions. Exploration of the supernatural allows authors to portray extraordinary beings and phenomena that captivate us and heighten our sense of awe and fear. Two vivid examples of what I am talking about are the Jewish legend of the Golem and Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein. But first, let’s begin by looking at a story in the Bible.

The First Book of Samuel (1 Samuel 28:3-25) recounts an event involving King Saul, the first king of Israel, and a witch or medium from Endor. In the story, King Saul found himself in a dire situation. The Philistines, Israel’s longstanding enemies, were preparing for war, and Saul was filled with fear and uncertainty. Seeking guidance, he consulted the Lord but received no response. Desperate for answers, Saul decided to seek out a medium or witch.

Although Saul had previously banned all witches and mediums from Israel, he disguised himself and went to the town of Endor. There, he sought the help of a woman who could communicate with the dead. Saul asked the witch to conjure the spirit of the prophet Samuel, who had died. Here’s an excerpt from the story.

And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and went, he and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night; and he said: ‘Divine unto me, I pray thee, by a ghost, and bring me up whomsoever I shall name unto thee.’…Then said the woman: ‘Whom shall I bring up unto thee?’ And he said: ‘Bring me up Samuel.’ And when the woman saw Samuel, she cried with a loud voice; and the woman spoke to Saul, saying: ‘Why hast thou deceived me? for thou art Saul.’ And the king said unto her: ‘Be not afraid; for what seest thou?’ And the woman said unto Saul: ‘I see a godlike being coming up out of the earth.’ And he said unto her: ‘What form is he of?’ And she said: ‘An old man cometh up; and he is covered with a robe.’ And Saul perceived that it was Samuel, and he bowed with his face to the ground, and prostrated himself.

Exciting, no? The story raises ethical and religious questions about the use of witchcraft or communication with the dead, for it conflicts with ancient Israel’s spiritual laws and beliefs. It also raises the hair on the back of my neck. Overall, the story of Saul and the witch serves as a cautionary tale, illustrating the consequences of seeking forbidden knowledge or resorting to practices considered taboo within a religious and cultural context.

Now, let’s examine a legend. Legends often combine elements of history and mythology, blurring the line between fact and fiction. They typically revolve around heroic or extraordinary individuals, events, or creatures and frequently carry moral or cultural significance. These stories often have a basis in actual events or people. Still, they are embellished or transformed over time through retelling. Legends serve as a way to explain natural phenomena, teach lessons, or preserve cultural heritage. They capture our imagination.

The legend of the Golem holds an important place in Jewish folklore and mythology, portraying a being created from clay or mud and brought to life through mystical or supernatural means. One of the most well-known stories associated with the Golem centers around Rabbi Judah Lowe of Prague, also known as the Maharal of Prague, who lived in the late 16th century. Rabbi Lowe’s creation of the Golem symbolized the Jewish community’s desire for protection and defense in the face of external threats.

According to the legend, the Golem of Prague was created by Rabbi Lowe to safeguard the Jewish people during times of persecution and threats. The Golem was brought to life through mystical rituals and the inscription of sacred Hebrew letters. As an obedient and powerful servant, it acted as a guardian and defender of the Jewish community, aiding Rabbi Lowe in ensuring its well-being. The legend of the Golem emphasizes the community’s hopes for protection and preservation. However, like the story of Saul consulting the witch at Endor, it also explores the dangers associated with the supernatural. In some versions of the story, the Golem becomes uncontrollable and potentially hazardous if left unchecked or if its creators fail to deactivate it properly. This duality presents the Golem as both a benevolent and helpful creature and a force capable of destruction.

Shifting our focus to Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, we encounter yet another exploration of the supernatural, this time from a Romantic era author. Shelley’s work delves into themes of human ambition, scientific knowledge, and the manipulation of nature. The story revolves around Victor Frankenstein, a character-driven by ambition and a thirst for knowledge. In pursuing scientific discovery, he ventures into the supernatural realm by animating a creature from lifeless body parts. This act defies the laws of nature, delving into the realm of the supernatural and surpassing the boundaries of the natural world.

Shelley’s portrayal of the supernatural in Frankenstein emphasizes the destructive power of playing God. The monster’s creation disrupts the natural order and violates the processes of reproduction and birth. The monster’s physical appearance, grotesque and horrifying, serves as a warning against tampering with powers beyond human control. Its existence brings about tragic consequences, disrupting lives and causing suffering and death. Moreover, the monster’s isolation and rejection intensify its negative emotions, leading to devastating events.

The Golem and Frankenstein stories are similar. Both explore themes of creation, power, and responsibility but differ in focus and context. Frankenstein delves into the moral and philosophical implications of scientific invention and the repercussions of human ambition. The novel warns against the consequences of surpassing the boundaries of nature and tampering with the supernatural. In contrast, the Golem emphasizes communal protection and preservation, raising questions about the responsibilities and limitations of wielding magical powers within a specific cultural and religious context.

The fascination with the supernatural allows writers to explore uncharted territories and evoke intense emotions. The Golem and Frankenstein stories stand as prominent examples of this exploration, each delving into the realm of the supernatural in their unique ways. The Golem represents the Jewish community’s aspirations for protection and preservation, reflecting their collective desire to ensure their safety. On the other hand, Frankenstein examines the consequences of human ambition and the manipulation of nature, serving as a cautionary tale against tampering with forces beyond human control. Both works emphasize the need for responsible stewardship of the supernatural and the potential dangers of overstepping boundaries. Therein lies the opportunity and the risk, then and now.

All the best,

Gershon