Photo by Marion Post Wolcott, Public domain. 1940.

My mother was born in Hazard, Kentucky, in the United States on November 14, 1930. She was the first of six children, three girls, and three boys. Six days before her eighteenth birthday, she married my father. She didn’t graduate from high school, though I’m not sure when she dropped out. When we lived in Mississippi, she took the General Education Development (GED) tests certifying that she had high school-level academic skills.

Subsequently, she completed a couple of courses at Millsaps College in Jackson. One was in drawing, the other in psychology. I remember once asking Mom what psychology is. She told me it’s the art of getting other people to do what you want them to do without their knowing it. I’m pretty sure that was not the definition her college professor gave her, nor the one in her course textbook, but it was Mom’s take on the enterprise. Judging by the way she handled my father and raised my sister and me, she was pretty good at it.

Mom was nineteen years old when I was born and twenty when my sister was born. I don’t remember either of my parents reading any books to us as children. I checked with my sister recently, and she confirmed my memory. What Mom did do, however, was sing fascinating songs to us, ones she had learned as a child growing up in Appalachia. I’ve written about some of the songs she sang to us as children in another blog.

But there was something else she did for us from time to time—recite poetry from memory. That says something, I believe, about the education she had received as a child. This made a great impression on me. I can still remember the first lines of a couple of the poems. One began, “The woman was old and ragged and gray / and bent with the chill of a winter’s day.” It was about a young boy stopping to help an elderly woman cross the street. Later I learned that the name of the poem is “Somebody’s Mother,” by Mary Dow Brine {1816 – 1913).

Another one began, “Under a spreading chestnut tree / The village smithy stands.” This poem was by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882). Longfellow was extremely popular in the 19th century. Later, his popularity declined, although Harold Bloom in The Best Poems of the English Language, includes four of Longfellow’s poems. Bloom says that Longfellow “remains a permanent poet, replete with grace and his own chastened mode of cognitive music.” There is a bust of Longfellow in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey near Chaucer’s tomb in London.

I was reminded of Longfellow quite by accident recently. I kept repeating some verses in my mind, like one does sometimes with a melody. I wasn’t sure of their source. I said them over to my wife, and she thought they sounded like something from Mother Goose. Here’s the rhyme:

There was a little girl

Who had a little curl

Right in the middle of her forehead;

And when she was good

She was very, very good,

But when she was bad she was horrid.

Attributed to Henry Wandsworth Longfellow

I did some research. Lo and behold—the poem is attributed to Longfellow. A note in Bartletts traces the source to The Home Life of Henry W. Longfellow [1882] by Blanche Roosevelt Tucker. Tucker states that “these lines were written by the poet for his children on a day when Edith did not want to have her hair curled.” Edith was one of Longfellow’s daughters.

What interests me in these lines is not their aesthetic quality, though I find their rhythm enchanting. Instead, it’s what they tell us, in a humorous way, about human nature. Indeed, we all know that humans are complex creatures. How is it possible for us to be such an intricate collection of good and bad traits? We can go from being “very, very good,” to being “horrid” in an instant. If you don’t believe me, try watching a wife and husband loading a dishwasher at the same time.

Not long ago, I watched the complete Rumpole of the Bailey TV series that aired initially between 1975 and 1992. In the programs, Leo McKern played Horace Rumpole, an English barrister who practiced law at the Old Bailey Criminal Court in London. The series was based upon books by the late John Mortimer. Mortimer, himself an English barrister, displayed a keen sensitivity to the good and bad in Rumpole’s clientele, some of them one-time offenders, others long-term professional criminals. What I liked about Rumpole, was that he did not view his clients as good or bad people, but rather as people who exhibited both good and bad qualities.

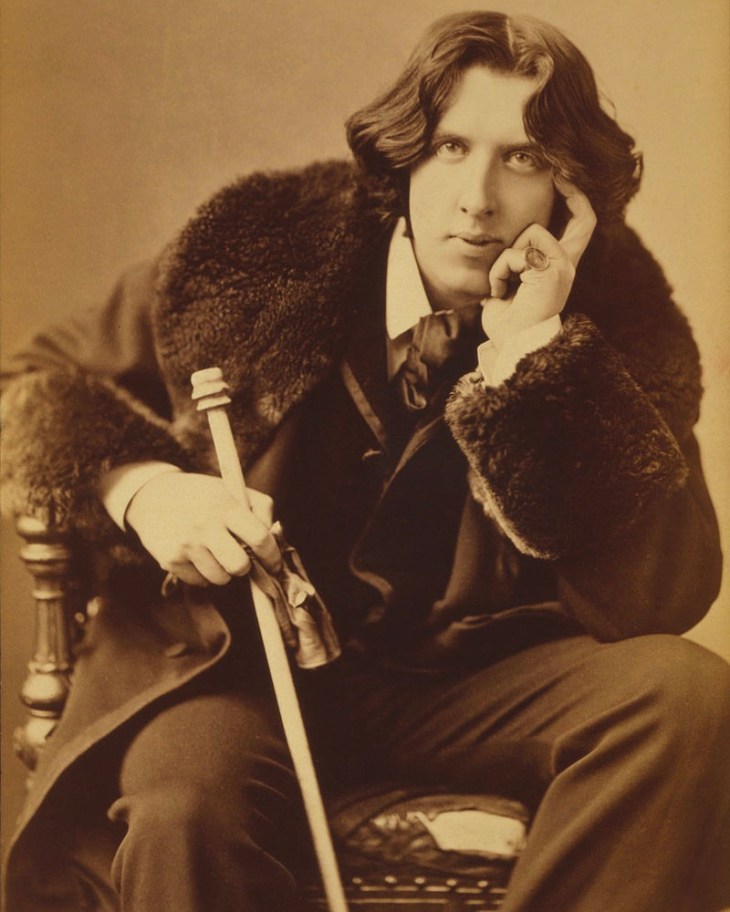

It is fitting, I believe, that John Mortimer wrote the Forward to Merlin Holland’s Irish Peacock & Scarlet Marquess: The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde. Holland, a grandson of Oscar Wilde, provides the details of Wilde’s first trial, the one in which Wilde charged the Marquess of Queensbury with libel. The full transcript of the trial provides the reader with a fascinating glimpse into Wilde’s personality, his ideas, how he thought, the kind of person he was.

Circa 1882. Public Domain.

Wilde underwent three trials. In the second and third ones, not covered in Holland’s book, Wilde was the defendant. The second trial ended in a hung jury; but the third resulted in Wilde’s conviction on charges of “gross indecency.” He served two years hard labor in prison.

There is a story Mortimer recounts in the book’s forward that I found very moving. He writes:

“There is a story about Oscar Wilde that, I think, should always be remembered. His friend Helena Sickert’s father had died and her mother, grief stricken and inconsolable, had shut herself away in her room and vowed that she would see no one. Wilde called and, insisting on seeing the mother, he got her to open her door to him. An hour, two hours passed and Helena waited for the inevitable tears and demands to be left alone. Then she heard an unbelievable sound; her mother was laughing. Wilde had entertained her, had pleased her, had made her feel that life was still worth living. He showed, in that and many other cases, that charm works wonders.”

—John Mortimer, Foreward to Irish Peacock & Scarlet Marquess by Merlin Holland [2003].

All the best,

Gershon

What a wonderful thing to be remembered for. Thank you for the story and for the entire piece.

From an obituary that I found strangely moving: the deceased person had operated a restaurant. He was celebrated for his kindness, his humor, and so on. Especially appreciated, however: his Boston cream pie.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Being able to recite poetry from memory is an increasingly rare skill.

I love the story about Wilde

Juliet

http://craftygreenpoet.blogspot.com

LikeLiked by 2 people